Here is a link to a freshly published article in the latest issue of Ex-Position

Author Archives: cldsnsn

New Publication: Buddhism and Vedic Mythology!

I am pleased to announce a new article, “Vedic Antecedents to Buddhist Mythology: Tvaṣṭṛ’s Cup, the Ṛbhus, and the Third Pressing in Comparison to the Several Myths of the Buddha’s Bowls,” published in the Taiwan Journal of Buddhist Studies. Click here to download a free PDF!

New Publication: Urbanism in Sumerian Poetry

In the Spring I co-edited a special edition of Interface, and my own paper on the Sumerian poem Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta is included in the edition, as is my editorial cowritten with the brilliant Charlène Clonts.

New Publication: Blank Space/Akkadian Metapoetics

In The Shape of Stories: Narrative Structure in Cuneiform Literature, ed. Sophus Helle and Gina Konstantopoulos. Brill. 258-281.

Preview Below (feel free to email me for an offprint)

https://brill.com/edcollchap/book/9789004539761/BP000011.xml

New Publication: N.H. Pritchard’s Poetics of the ostrakon

See my new essay in Jacket2

New Publication: Pasolini’s Greeks and the Irrational

Open Access: https://journals.uni-lj.si/clotho/article/view/11518

Abstract:

This article traces Pasolini’s engagement with Aeschylus Oresteia and the concept of the “irrational,” through which he sought to excavate patterns of ideological resistance in the classical past. I argue that Pasolini’s translations and adaptations of Aeschylus ultimately failed to achieve his desired ambition to forward an Aeschylus fit for the proletariat, and whose words might spark new kinds of Marxist thought. However, there is value in reading into Pasolini’s practices and his reflections on his work. Acknowledging and parsing his affects of disappointment and resignation, the broader conceptual outlines of his ambitions become clearer as gestures of kind of “failed” classical reception – an attempt to turn the classics to new political ends. An analysis of this kind of failure teaches us broader theoretical lessons about what it might mean to perform a generative and politically fruitful appropriation of the classics, necessarily confronting the entrenched ideologies of the past and their tenacious ability to reproduce themselves even in the most unexpected literary and political contexts. The article engages with selections from Pasolini’s literary, personal, and political writings from the 1960s until his death – connecting his translations and adaptations of Aeschylus to other contemporaneous essayistic, novelistic, and cinematic projects.

A Field Guide to N. H. Pritchard’s Works

Current Version August 3 2022.

This page serves as a bibliographic research tool for readers interested in exploring the poetic works of N. H. Pritchard. I have assembled this guide collating information from other online repositories and bibliographic tools (cited among the bibliographic sources). The main features are: (1) a listing of all known works, whether published or otherwise; (2) links to available PDFs of published works; (3) a bibliography of known scholarly works on Pritchard.

I have prepared this as part of my work on Pritchard’s unpublished Mundus–on which, much more to come (here and elsewhere). Please feel free to submit suggestions, corrections, or additions!

Poems in Published Books

Pritchard published two books. Their contents are reproduced below so as to allow easy comparison to poems published separately. Reading copies of both books available through the Eclipse Archive.

The Matrix / Poems: 1960 – 1970 (Doubleday, NY. 1970)

I. Inscriptions 1960-1964

-

-

- Wreath

- Vista

- Harbour

- Self

- Windscape

- Ology

- Volitive

- Agon

- Louisburg Square

- Subscan

- Cassandra and Friend

- Evening

- Aswelay

- Matrix

- Point

- Swampscott Autumn

- Outing

- Gist

- Visage

- Design

- Gathering

- Preposition

- The Way

- De Tu & I

- Mist Place

- The Voice

- Camp

- 3

- La Alba

- Totemic

- Autumnal

- Doooooooooooooooom

- Once

- Dia

- Asalteris

- Metagnomy

-

II Signs 1965-1967

-

-

- The Signs

- Gyre’s Galaxy

- Season

- Trace

- the own

- Silhouette

- Passage

- Metempsychosis

- Sail

- Each

- Soliloquy

- Visitary

- The Harkening

- Dusk

- Paysagesque

- The Cloak

- Burtn Sienna

- The Narrow Path

- Epilogue

- Now

- N OCTUR N

- Aurora

-

III Objects 1968-1970

-

-

- #

- y

- Terrace Figment

- Isostasy

- Ω

- C

- L’Oeil

- @

- “

- Love

- o

- b

- Peace

- O

-

EECCHHOOEESS (NYU Press, 1971)

-

-

- .d.u.s.t.

- MINT

- THE WATCH

- FEAWE

- junt

- WE NEED

- arodnap

- carbon

-

Works Published in Periodicals and Anthologies

Publication info given parenthetically in short form, see the key directly below linking further to bibliography. Many of these are scanned and available through the Eclipse Archive. The key is based on the Eclipse entries, where relevant (i.e. virtually throughout, exceptions contain links to further PDFs where available). N.B. Untitled concrete poems are labeled by ad hoc titles in square brackets.

-

-

- Hoom (“short story,” Necromancer)

- Magma (Liberator)

- De tu and I (Liberator, and then Matrix)

- Season (Liberator)

- Gathering (Liberator)

- Sail (Liberator, and then Matrix)

- Awelay (Dices, and then Matrix)

- # (Dices, and then Matrix)

- Alcoved Agonies (Dices)

- : (Dices)

- As (Dices)

- Parcy Jutridge (Dices, also included in a letter sent to Ishmael Reed, see below)

- .-.-.-. (Dices)

- OVO (Dices)

- .. (Transrealistic)

- oOo (Transrealistic)

- [line+dot untitled] (Transrealistic)

- [oices v] (Youth)

- [T] (Youth)

- [TTTTT] (Natural)

- bBb (Natural)

- , (Natural)

- No. (Natural)

- [TTTTT (2)] (Natural)

- vvvv (Natural)

- O (Believe, and then Matrix)

- Bones (Clown)

- Selected Speeches (Clown)

- Quanta (Clown)

- lore (Clown)

- Gyre’s Galaxy (Texts)

- Visitary (Texts)

- The Vein (East Village, “part of a novel,” see Mundus below)

- Mist Place (Northwest, then Matrix)

- Subscan (Northwest, then Matrix)

- Ology (Northwest, then Matrix)

-

Key: Necromancer = Ishmael Reed’s 19 Necromancers from Now [Garden City: Doubleday, 1970]. Liberator = Liberator [Volume 7, Number 6 (June 1967): 12-13]. Dices = Dices or Black Bones: Black Voices of the Seventies, ed. Adam David Miller [Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1970]. Transrealistic = Vol 1. of Yardbird Reader, ed. Reed [Berkeley: Yardbird Publishing, 1972]. Youth = Richard Kostelanetz’ collection In Youth [New York: Ballatine, 1972]. Natural = Ted Willentz and Tom Weatherly’s Natural Process: An Anthology of New Black Poetry [New York: Hill and Wang, 1971]. Believe = Paul Bremen’s You Better Believe It: Black Verse in English from Africa, the West Indies and the United States [London: Penguin, 1973]. Clown = Clown War Nos. 3-5 [1973-1974]. Texts = Text-Sound Text, Ed. Kostelanetz [New York: Marrow, 1980]. East Village = The East Village Other, Vol III No. 7, Jan 19-25, 1968. Northwest = Poetry Northwest Spring 1966 VII 1 pp. 12-123.

_____DRAFT GUIDE ENDS HERE: SEE BELOW FOR UPCOMING DEVELOPMENTS____

Other Media [Under Construction]

Interviews / Spotlight Pieces

Audio Recordings

Film Recordings

Known Unknowns [Under Construction]

Unpublished but known to exist in draft/manuscript form

- Mundus

- This is a work that presents a long series of bibliographic challenges. I give below my preliminary notes, since I am working on this piece at length.

- Title: The work is mentioned in letters and in author bios (as well as on signed/labeled sheets and cover sheets) with several different names that include: “Mundus”, “The Mundus”, “Mundus: A Novel”, “Mundus Fragment(s)”, “Mundus Fragments Watertight” and other similar variants.

- Published Portions/State of the Work: “The Vein” (listed above) is the only in-print portion of Mundus (in a letter Pritchard explains it is a conglomerate from several portions of a long 200 page work). “The Vein” corresponds in part to the pages of Mundus on display at the Whitney, although the colors and ink additions are not represented. Other inked and colored pages of Mundus exist in the Pritchard Estate, although the full scope of the work as extant is not known. In later letters to Reed (early 1970s) Pritchard mentions that it has gotten longer (250-300 pages) and that he is reworking it. Perhaps the colored pages are part of this reworking. Certainly, the date on the Whitney Museum label (1970) does not correspond with Pritchard’s own signatures and dates on some sheets (into 1971). Pritchard reads from Mundus in the film mentioned above.

- This is a work that presents a long series of bibliographic challenges. I give below my preliminary notes, since I am working on this piece at length.

- Poems/Texts on display at the Whitney Museum (dates given as per museum label, square brackets indicate ad hoc label for identification purposes)

- Mundus: A Novel (1970) (22 pages)

- Untitled (no date) [……] (Estate)

- Biography of Public Readings & Discussions (covers 1963-65)

- Untitled (Novae- and Gyre-) [) (] (1968)

- Untitled [c s o] (1967)

- Prejudice (no date) (Estate)

- Untitled (1968) [red dots] (Private Collection) – 2 pages

- Untitled (no date) [-] (Estate)

- Red Abstract/Fragment (1968-69) (Private Collection) (n.b. Mundus, above)

- Poems in the Pritchard/Reed letters (University of Delaware Special Collections)

- Still

- Bridge (a draft of the text given the title “Red Abstract/Fragment” in the Whitney Museum)

- Game

- Parcy Jutridge (later published, see above)

Mentioned (e.g. in letters/documents) but never seen by me in any form.

Bibliography [Under Construction]

Primary Materials Online / Important Links

- Eclipse Archive PDFs

- East Village Other Open Access Archives

- Ugly Duckling Press (Reprint of The Matrix)

- Mast Books (Eecchhooeess Reprint) [Link broken?]

- The New School Archives (Even Announcements, Course Descriptions, ca. 1969-73)

Scholarly Publications on Pritchard [Under Construction]

***Acknowledgements are due to many extremely helpful librarians at the University of Delaware, NYU, The New School, Columbia University–and to the Pritchard Estate.***

ACLA Seminar Proposal

Hello Readers,

Just dropping the link to the ACLA Seminar proposal that Sophus Helle and I are hoping to organize for the 2022 ACLA! https://www.acla.org/philology-affect-comparative-perspectives

More about Sophus here: https://sophushelle.com/about/

Hope you can spread the word and looking forward to submissions!

An Antifascist Topography?

[Part I of a Series of Blog Posts on Modern Epigraphic Problems, tangentially related to a book project on the Pyramid in Rome.]

I took this photo in Piazza Pascoli in Matera. For those who are not familiar with this kind of sight, the picture shows an intentionally destroyed fascist monumental plaque. The erasure is such that the original persists, ghost-like. The three vertical rectangles held three white fasces. Beneath the three ghost fasces three letters can be perceived, « A XIV », a date in Roman numerals, the 14th (XIV) year (Annum) of the Fascist regime.

For comparison, consider this similar addition to the restoration of the Teatro Marcello in Rome.

From beneath the spectral remains of such iconography in Matera you can look out onto one of the most beautiful views in Italy. The temptation to look up and fuss over the messy face of the wall is minimal.

The irony of the erased monument’s transparent persistence is that it speaks to a much more general problem. The overall effect of efforts to erase fascist symbols and iconology are much the same throughout the country. While the most offensive and clear-cut insignia may have been stripped from (some) monuments and facades, the contextual evidence (be it something like what is pictured above or the massive presence of rationalist super-structures such as Rome’s Ostiense Station) speak plainly to a period that cannot be forgotten, or repressed.

Further, for a nation apparently bent on erasure, some of the most pronounced monuments persist unaffected by the attempts to reframe historical memories. We need but recall the Mussolini Obelisk of the Foro Italico.

Persistent erasures, in addition to the remainders, provide a window into a subtler, more pernicious and messy relation to history. So much of the urban topography of the city of Rome, and of Italy more broadly, was designed in the period of the Fascist regime. The aesthetic priorities of the period continue to govern our lived experience of the urban landscape, whether from a look out point like that of Matera or even in a more quotidian sense, for instance walking along the raised banks of the Tiber near Testaccio where a similar monument announces the Fascist restoration of the walkway.

Personally, I grew up by the Ostiense Station and only learned by word of mouth that it was built for Hitler’s official state visit visit to Rome and marked the beginning of his parade route that would take him past the Piramide and into the heart of the ancient pomerium. I then learned a bit more about it when I chanced upon Ettore Scola’s Una Giornata Particolare. Many Romans with whom I talk about the area do not know that Piazzale dei Partigiani used to be called Piazzale Hitler, and that Viale delle Cave Ardeatine was similarly Viale Hitler. The spaces have been renamed after Partisans and victims of Fascism–but the fact they are a specific topographical marker of Fascist urbanism is forgotten. (See here for a blog post in Italian covering more examples of streets that changed named.)

Recently, I walked around the entire Ostiense neighborhood, Testaccio included, collecting notes for a book on the Piramide and documenting visible and legible traces of the transformation in the urban landscape.

I asked myself the following question: what can I learn about recent history from the streets themselves–without a history book or the internet, but looking to the signage, the plaques, the inscriptions?

I discovered that there is no explicit signage left that connects Ostiense to its origins, explaining the history. Plaques near the Pyramid help establish–in the vaguest terms–the importance of the area in World War II. As an example, The Battle of Porta San Paolo is memorialized with a date, but is not named as such nor its significance explained.

Overall, the sense is that history took place around these spaces rather than within them. Walking through them we enter into a vacuum of sorts, as if the ghost of Fascism could be remitted to a vague past before the city, a fabricated antiquity that comes dangerously close to some of the artificial constructs of Fascism itself.

In a seeming paradox, the dilapidated plaque in Matera speaks eloquently about the past and poses sets of questions that are as timely as they are difficult–questions about the way we occupy spaces and transform them, particularly in the conversion of inimical affective environments into ones that can become the stages for public education and sites of civic reflection.

[TO BE CONTINUED]

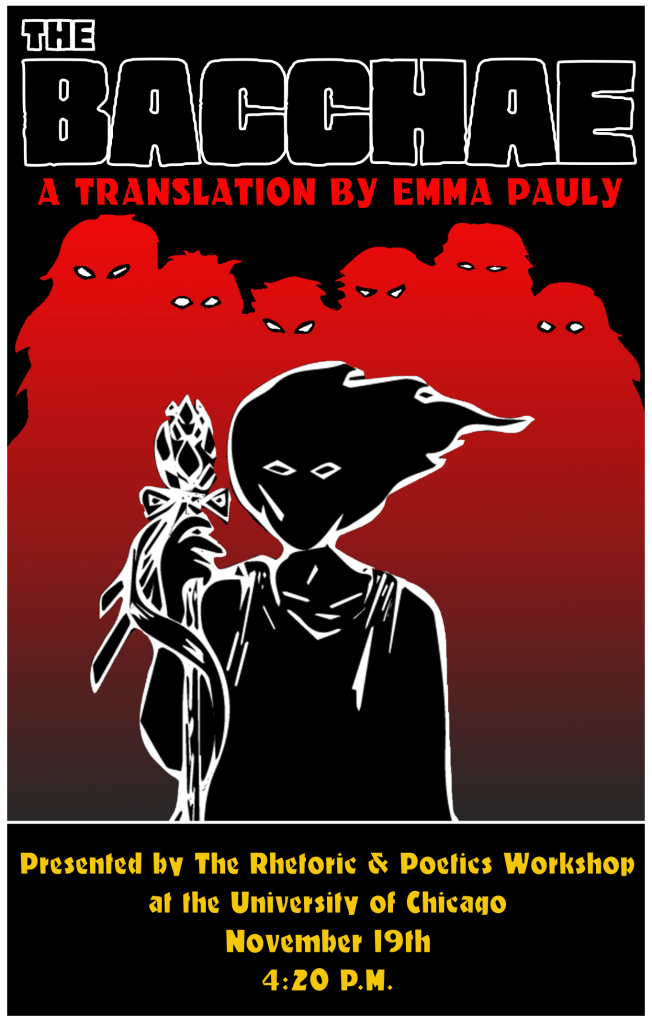

Emma Pauly’s Bacchae at Rhetoric & Poetics (Nov 19 2020)

Recording (w/ Screen Captions)

Closed Captioning by Larry Eames.

Archival Info

The performance was preceded by an Introduction by Emma (included in the video above) and followed by a 45-min discussion with some members of the cast and select audience members (not included).

Blurb

A young person returns to their hometown for the first time in a long time, hoping to find acceptance. When they find the opposite, tempers flare, consequences ensue, and identities are questioned, changed, and dissolved. This translation of Bacchae centers a non-binary/gender non-conforming reading of Dionysus and roots itself in the worlds of gender, grief, and the family unit.

Directed & Translated by Emma Pauly

Cast List

Dionysus: Sarah “Sam” Saltiel

Pentheus: Claudio Sansone

Agave: Samantha Fenno

Kadmos: Lynn Fitzgerald

Tiresias: Eric Q. Vanderwall

Chorus Leader: Sally Rose Zuckert

First Messenger/Chorus: Hannah Halpern

Second Messenger/Chorus: Amber Ace

Soldier/Chorus: Jack Chelgren

Performance Poster

Poster designed by John Koelle.